Human composting offers an environmentally friendly end. Some are pushing to legalize it in Illinois

Published in News & Features

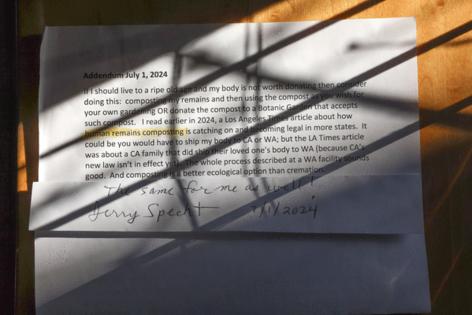

CHICAGO -- Two summers ago, a newspaper article inspired Roxann Specht to write a detailed note containing her end-of-life requests. After sharing it with her husband, Gerald, he was similarly inspired but much more to the point.

Six words scrawled underneath her note would become his dying wish: “The same for me as well!”

Seven months later, Gerald Specht died unexpectedly at 75 after collapsing outside his Evanston home. Survived by his wife and three children, Specht’s note referred to instructions not to bury or cremate his body but rather transform it into compost and return it to the earth — an increasingly popular, environmentally friendly alternative to handling human remains.

Not only is human composting affordable, but it also avoids the release of plumes of smoke from cremation and the leaking of fluids from burying embalmed bodies. In the United States, each year, cremation releases hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and funerals put hundreds of thousands of gallons of toxic chemicals into the ground.

And for nature lovers, it is a way to return to whence they came.

“It felt right because of who my dad was,” Mark Specht, one of his children, told the Tribune. “Growing up, he was always doing a lot of gardening at our house. Earlier in his life, he had worked on various farms. So it felt very in line with who my dad was.”

Specht’s family reached out to some human composting companies, determined to honor his wish despite its novelty. Washington was the first state to legalize the process in 2020, and Sweden is the only country outside the United States where it is legal.

While Illinois has not legalized the processing of human remains into compost, companies can still transport bodies to facilities in one of 14 states where it is legal. But out-of-state transportation increases expenses and runs counter to carbon neutrality goals, and might make it harder for loved ones to let go of the deceased’s remains.

Earth Funeral, based in Washington state, has taken on a few out-of-state clients like the Spechts, who reached out proactively. On Tuesday, it officially rolled out direct logistical services for Illinois residents. A couple of other companies from Washington already do this, including Recompose, whose founder, Katrina Spade, invented human composting in 2017.

“This is a taboo subject for a lot of people, that they’re just not that comfortable talking about,” said Earth Funeral CEO Tom Harries. “It’s less pushback on the specific process and more discomfort around talking about your end of life.”

However, it’s something he is comfortable discussing, having previously founded a funeral logistics company in his native England and later a direct consumer cremation provider in San Francisco. He kept hearing the same question from families: What could they do that was better for the environment than cremation or traditional burial?

It was a question that also nagged at Spade, and ultimately motivated her to develop the process. About the method’s growing popularity, she told the Tribune, “the sky’s really the limit.”

The process of human composting — some prefer to call it soil transformation, terramation or natural organic reduction — can provide an answer while essentially imitating nature.

“The idea of being gently transformed into soil and returned to nature resonates with a lot of people on a personal level,” Harries said. “This is exactly what would happen on the forest floor, but we are accelerating it through science and technology.”

At a facility in Washington or another state where the process is legal, the body is placed in a sealed cylindrical vessel that looks like an opaque hyperbaric chamber, alongside organic mulch, wood chips and wildflowers. The remains provide nitrogen, and the natural materials provide carbon — the two main components of compost.

The vessel allows for controlled and optimized temperature, moisture and air flow to create the right conditions for microbes to break the body down. After 30 to 45 days, the process is complete, and even bones are reduced to a fine powder, like in the cremation process.

Beyond being more environmentally friendly, human composting addresses other drawbacks to traditional options. For instance, at a couple of thousand dollars, human composting services are often less expensive than traditional burials, which usually entail embalming, caskets, cemetery plots and headstones, and are competitive with cremation costs. The national median cost of a funeral with a viewing and burial in 2023 was $8,300, while the median price of a funeral with cremation was just under $6,300. Human composting services can cost between $5,000 and $7,000.

And burial requires real estate that “is just not a good use of land, in the context of 330 million deaths in this country over the next 80 years,” Harries argued, citing a figure based on the U.S. life expectancy average of 77 years.

“We’ve massively moved away from burial as a society,” Harries pointed out.

In the mid-1980s, the rate of burials in the United States was still over 80%. But since the 1990s, that has increasingly shifted. By 2024, the country’s cremation rate was almost 62%. Spade said she believes human composting can similarly surpass cremation rates over the next few decades.

As of 2023, Illinois had a 65% cremation rate, slightly above the national average, according to the Cremation Association of North America.

“We are increasingly transient,” Harries said. “… We don’t live where we necessarily grow up or have family. So the concept of having a specific place to visit is just less important to people. We’re less religious and less ritualized as a society.”

Still, there is resistance from religious institutions; for instance, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops considers burial the “preferred method” and finds cremation acceptable under certain conditions, while opposing human composting. The Catholic Conference of Illinois has opposed efforts to legalize the process in the state, saying the method “degrades the human person.”

Though a bill to make human composting legal passed the Illinois House with overwhelming support, 63-38, in 2023, it stalled in the Senate. As the spring legislative session kicks off, state Rep. Kelly Cassidy, a Chicago Democrat who sponsored the initial bill, said lawmakers plan to reintroduce it again with a little “retooling.”

“Nobody’s forcing any religion to provide this service,” Cassidy said, adding that the Catholic Church was historically opposed to cremation for centuries until the 1960s.

Rep. Mary Beth Canty, an Arlington Heights Democrat, will be the lead sponsor of this year’s bill.

“People do get nervous because it’s new,” Canty said. “So my goal is to make sure that people really understand we are not trying to force anyone to handle their after-death care in a particular way. We just want to make sure that people have the options that they want to have.”

Spade said she thinks more states will pass similar legislation this year. “We didn’t think it’d go so fast,” she said of the legalization of human composting in 14 states over the last six years.

Harries said death is deeply personal, and what resonates with one person might not with another.

“Our main belief with what we do is: this is consumer choice,” he said. “If you would like to choose it, you should be able to choose it — and you should be able to choose it locally as well.”

Michael Sharkey, general counsel for the Illinois Funeral Directors Association, said families place their trust in the state’s licensed professionals at some of the most vulnerable moments of their lives, which deserves consistency and compassion.

“We believe there is room for innovative ways to honor a loved one’s choices and we respect all forms of final disposition as a matter of dignity in death,” Sharkey said in an emailed statement. “The funeral directors of the IFDA welcome these emerging forms of disposition so long as such is carried out with dignity, oversight, and solid regulatory safeguards.”

‘Ashes to ashes, dust to dust’

When Kathleen Thompson’s breast cancer metastasized to her liver, her partner of 46 years, Mike Nowak, had to plan for the unthinkable. As the longtime artist and activist, typically so lively and effervescent, entered hospice, he started researching natural burial options.

“Before she died, I thought she was going to pull through. I thought she was going to beat this. I really did. And then everything went south very quickly,” Nowak recalled. “Kathleen and I had never really talked about (soil transformation), but I knew that there was going to be no objection. She and I were on the same page about everything.”

Thompson died in December 2024, shortly before the holidays, at 78.

When he connected with Earth Funeral and learned Thompson’s body would have to be transported to Washington to be processed, Nowak felt that it was meant to be. The company has a plot on the Olympic Peninsula where some of the compost from clients is returned to the land.

“And I’m not a huge believer in fate, OK?” Nowak told the Tribune. “Well, Kathleen and I had a vacation home on the Olympic Peninsula for 17 years.”

At that point, his decision was made. Words heavy with nostalgia, Nowak recalled their visits to Lake Quinault: “It’s hard to describe, because it was paradise to us.”

Some families choose to keep a portion of the compost for themselves, but there is usually so much produced that part of it gets used at conservation sites, like at the peninsula.

To state Rep. Cassidy, human composting is an opportunity to be “creative and thoughtful,” she said, “instead of rigid and change-abhorrent.”

“We’re still working through some pressures,” she said, “for example, the cemetery industry doesn’t like it because they think it cuts into their business. Whereas what we’ve seen in other states (is that) it actually is very complementary.”

Besides using the compost in reclamation projects, loved ones often use it in memorial gardens to honor the deceased.

“There’s a lot of really cool stuff you can do,” Cassidy said.

After Gerald Specht’s body was sent to Washington and processed, his family received some of the resulting compost, which they spread at his wife’s home in Evanston during a small ceremony. Special attention was given to a mulberry tree that Specht used to care for.

“I feel like that was one of the more emotional times, because I think we all knew that it was something that my dad would have really liked,” his son Mark said.

Mark Specht said his mother’s pastor at a local First United Methodist Church was very supportive of the process, even though “some religions don’t look as kindly upon this approach.”

And Roxann Specht still wants her body to be turned into compost when she dies.

“Everyone in my family thought that this is a great idea and should be more widespread, more available, and more normalized,” Mark Specht said.

Harries, the Earth Funeral CEO, said it has been great to work with clients like the Spechts and Nowak, who resonate with the process so much that they agree to fly their loved one across the country.

“They shouldn’t have to do that,” he said. “You should be able to choose something that resonates with you, and you shouldn’t have to fly your loved one to the other side of the country to undergo the process.”

Nowak, who has gotten involved in organizing for the legalization of the procedure in the state, said that for it to be truly environmentally friendly, bodies can’t be flown thousands of miles away.

“We need something in the Midwest,” Nowak said. “For those people who want an alternative, we need to have an alternative, and it makes sense for Illinois to step up and be part of that.”

He said he is joining the fight to honor Thompson, like he hoped to do by choosing soil transformation.

“For people who think it doesn’t honor the remains, I think it’s just the opposite. It absolutely honors (the) remains,” Nowak said. “To be returned to the earth — isn’t the phrase ‘Ashes to ashes, dust to dust’? This is the perfect embodiment of that.”

The great equalizer

According to the National Association of Funeral Directors, over half of Americans — especially young people like millennials and Gen Z — have expressed a preference for green burial options, and 72% of cemeteries have reported more requests for natural burials. These often avoid using embalming chemicals, and options include human composting, burials in biodegradable containers, or a process that breaks down the body using lye, heat and water, dissolving soft tissue while leaving bones to be ground into fine powder.

As the industry evolves, it’s adapting more and more toward offering these green options under increased demand, said Stephen Kemp, a funeral director based in a suburb of Detroit and a spokesperson for the association.

“I always tell people, ‘From the time you’re born to the time you die, you’ve written a story. However you want to celebrate that story is very important,'” he said.

Even older generations have shown growing interest in nontraditional, natural burial alternatives as part of their end-of-life planning. And those in the business argue it is important to be proactive in choosing a preferred method of disposition, or the way their remains will be handled.

Death is inevitable, after all.

“This is not something that might happen. This is something that will happen,” Harries said. “So having some form of plan around it just makes it easier for everyone.”

Day in and day out, for over 40 years, 73-year-old Dennis Beaupre clocked in at a flower shop across a cemetery in Peoria. Work entailed leaving bouquets on graves and arrangements on caskets in funeral homes. Mourners stopped by to buy flowers. From the storefront, he would watch people get buried and funeral processions every day.

Inevitably, he pondered death and human mortality a lot more often — and earlier in life — than the average person would.

“Maybe if I didn’t see it every day, maybe I wouldn’t think about it that much,” the now-retired florist said. “It was kind of something we got used to.”

It also meant he became very familiar with traditional funeral practices, he said, “but none of that appealed to me, as far as getting buried in the ground, in a coffin or a casket.”

A couple of years ago, while visiting his sister in Florida, he began watching the television show “Six Feet Under,” which is how he learned about natural burial options.

“I thought, ‘Now, that I really like,'” Beaupre said. “Because not only is it all natural, but they’re using your remains to do some good in the world, and then they give a little portion back to your family if they want it. And that really made sense.”

It’s a decision motivated, in large part, by several trips to Alaska during which he has visited the same glacier “over and over again.”

“And every time I go, it’s shorter and shorter. It keeps receding back and back,” Beaupre recalled. “It’s undeniable what we’re doing to the planet.”

Cremation uses natural gas, a fossil fuel, to reach the high temperatures needed to burn a body. Processing just one body like this can release an average of 400 to 600 pounds of carbon dioxide, equivalent to an almost 600-mile car trip — like driving from Chicago to Nashville. In the atmosphere, carbon dioxide traps heat, increasing average global temperatures that melt glaciers.

The combustion also emits carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, fine soot and mercury.

All “his people,” Beaupre said, already know it’s what he wants for his remains. “So it’d be no surprise,” he said.

But no burial won’t mean no celebration of life, which he has made preparations for as well: “I’ve picked out a bunch of pictures and music that I want to be played.”

That playlist, still ever-growing, includes hundreds of songs, most from the 1970s.

“I hope that my nephews and nieces might want a small package of me so they can plant a tree someplace, or they can scatter me in the woods,” Beaupre said. “But I think for the bulk of what’s left, I would just like to be used wherever it’s needed, to refurbish the land, … create a park or to reclaim a landfill.”

Like Beaupre, 73-year-old Evanston resident Valerie Fronstin says she isn’t planning to die anytime soon. But she’s also already making arrangements to be turned into compost.

She hopes it’ll save her family some stress compared with having to pick out a casket and headstone, or an urn. “It’s a lot of things when you’re in the middle of grief,” she said.

“I don’t want to take up any more space in the world. I want to give back, and I really like the idea of turning back into compost,” she said. “And I told my daughter if she wants any of me, go for it. But otherwise, I would be glad to be in a forest, somewhere outdoors.”

The way people want their remains handled is their last wish, and should be respected, she said.

“I’m tired of people telling me what I can do with my body,” Fronstin said. “I should be able to go out the way that I want.”

In an emailed statement, Bob Gordon Jr., president of the International Cemetery, Cremation and Funeral Association, said that perspectives on human composting vary, including among members of the organization.

“Honoring the deceased is a deeply personal decision, and families should have the ability to choose the form of disposition that best reflects their values, beliefs, and circumstances,” Gordon wrote. “Each option carries its own considerations, and no single method is right for every family. ICCFA affirms that families deserve access to clear and factual information about all legally available disposition options so they can make informed choices.”

Jennifer Walling, executive director of the advocacy nonprofit Illinois Environmental Council, said the organization has been working with state lawmakers to pass a bill for the last three years.

“It’s frustrating to see this choice taken away,” she said.

Rep. Cassidy said she first learned about human composting — and later, became the leading proponent for Illinoisans to have that choice — “in the most representative democracy way possible,” after a constituent approached her at a town hall about it. And Rep. Canty has a similar story: One of the first emails she received from a voter after being elected in 2022 was about legalizing the natural burial option.

Canty said it’s ultimately a matter of personal choice. “And it’s also about, for some folks, being able to live on in the world.”

©2026 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments