Michael Hiltzik: How the economy went from a 3% annual growth rate to the brink of recession just two days later

Published in Business News

For a brief, shining moment last week, it seemed as if the U.S. economy had dodged a tariff-powered bullet. Gross domestic product grew at an annual rate of 3%, the government announced Wednesday, rather higher than the 2.3% projected by economists.

"WAY BETTER THAN EXPECTED!" President Trump crowed on Truth Social. He claimed that this justified a reduction in interest rates by the Federal Reserve Board, lower rates being one of his hobby horses. (Never mind that faster growth generally prompts the Fed to raise interest rates to keep the economy from overheating.)

"The Trump Economy has officially arrived," Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick posted on X after the GDP report. "Congratulations America: 3 percent today, and we're just getting started."

Not so fast, Mr. Secretary. The euphoria lasted only 48 hours. On Friday, the Labor Department released preliminary employment figures for July (gaining a meager 73,000 jobs) and revised figures for May and June (revised down by 258,000 jobs), to a two-month total of only 33,000 jobs. This was "unambiguously bad news," said economist Dean Baker of the Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Several economists have observed that parsing economic statistics is especially complicated just now, because it requires factoring out the short-term effects of Trump's tariff policies — not merely the rates being charged, but anticipatory actions by importers, manufacturers and consumers.

But generally speaking, it's evident that the GDP release overstated second-quarter growth and consequently the rate for the first half of this year. Closer scrutiny of the job numbers published Friday indicates that employment is even weaker than the headline figures indicated.

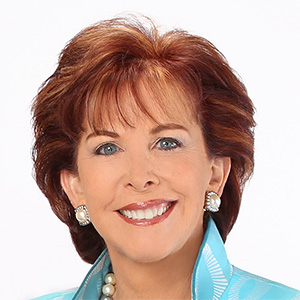

As has been widely reported, Trump reacted to the employment numbers with an epic snit, ordering the firing of Bureau of Labor Statistics Commissioner Erika McEntarfer, whose devotion to rigorous statistical reporting is a byword in the economics profession.

Things are not likely to look much sunnier in the days to come. Trump's claim that the BLS, a unit of the Labor Department, rigged the jobs numbers to make him look bad will face a major test this week and next, when a tsunami of BLS data will reach landfall.

On Thursday comes BLS' reading of productivity and labor costs; next Tuesday brings the consumer price index and real earnings, two inflation measurements; next Wednesday brings state-level job openings; followed a day later by the producer price index, another inflation gauge; and a day after that U.S. import and export price indexes.

With the exception of the state job figure, all these metrics pointed to higher inflation and an economic slowdown in their most recent monthly or quarterly reports. It's possible that any of them might reverse and show economic strength since the last reports, but a safer bet is that they will largely affirm the readings that so irked Trump.

"Today's jobs report is what entering a recession looks like," wrote Josh Bivens, chief economist at the labor-oriented Economic Policy Institute, on Friday. "Could we pull up? Sure. But if we look back and end up dating an official recession that starts 3-6 months from now, this is what it would look like today — rapid softening/deterioration in the labor market."

The 3% top-line number for second-quarter annualized growth was "flattered by an increase in net exports," observed Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist for RSM, a business consulting firm — that is, exports fell modestly in the second quarter, but imports plummeted. Setting aside the trade distortions, Brusuelas calculated, the GDP figure for the quarter looks more like annualized growth of only 1.2%, not 3%.

The long-term impact of Trump's tariffs is grim, according to projections by the Yale Budget Lab. At the end of July, the White House boasted of having collected $150 billion in tariffs so far this year. That might seem to be a big number, but let's put it in perspective.

Total federal revenues through June this year, including the tariff receipts, were more than $2.9 trillion, according to the Treasury Department. The tariff collections amounted to about one-twentieth of that, more or less.

The long-term projections are more telling. The Budget Lab calculated that at current levels, the Trump tariffs would raise about $2.7 trillion through 2035. But they would exert a $466-billion drag on the economy, for a net gain of about $2.2 trillion. But that leaves open the question of who would be paying those tariffs. The answer is: Mostly Americans, who would pay through higher prices on imported goods and domestic goods made with tariffed raw materials and other inputs.

In the short term, the Budget Lab notes, tariffs are regressive — they strike disproportionately at lower-income people. The lowest-income 10% will see their disposable income fall by about 3.4 percentage points, an average annual cost of about $1,300 per household. For the richest 10%, the cost is only about 1 percentage point.

That effect has much to do with which products are subject to the tariffs. "Consumers face particularly high increases in clothing and textile prices in the short-run," the Budget Lab reckons. "Food prices rise 3.3% in the short-run and stay 2.8% higher in the long-run."

As for the impact on individual sectors, the tariffs will help manufacturing, in which long-term output would rise by about 2.1 percentage points if the current tariffs remain in place. But that increase would be swamped by declines in agriculture (down 0.9 percentage points), mining and extraction (down 1.3 points) and especially construction (shrinking by 3.5 points).

The Budget Lab expects the unemployment rate to rise by 0.3 percentage points by the end of this year and 0.7 percentage points by the end of 2026. By the end of this year, employment will fall by 497,000.

The damage from the tariffs thus far, the Budget Lab estimates, has fallen most heavily on Canada, with a projected long-run decline of more than 2 percentage points in GDP. The second-worst hit will be suffered by the United States itself, with a long-run shortfall of 0.4 percentage points. That's nearly double the hit faced by China, which Trump has contended is America's most important economic threat.

Before delving more deeply into the jobs reports, let's address the claim of Trump and his acolytes that the BLS numbers were somehow manipulated; they point to the unusually large revisions of the May and June statistics, among other factors.

Virtually no economists outside the White House buy that claim. They understand the statistics-generating process at the BLS. As economist Betsey Stevenson of the University of Michigan (a former chief economist at the Labor Department) explained online, the bureau issues preliminary data subject to two rounds of revisions in order to have a reasonably current picture publicly available, even if it's incomplete.

Not all employers surveyed by BLS manage to get their figures to the bureau by the 12th of every month, the usual deadline. Some are too busy, some issue paychecks only monthly, among numerous factors. The revisions also incorporate fine-tuning of seasonal adjustments, the BLS says.

"Should the data be held until all companies in the survey respond?" Stevenson asks. "That would mean releasing May data now, in August. It would be more accurate ... but it would mean waiting months for the data."

Normally the revisions are modest. What has the White House vibrating is the scale of the revisions. But the revised figures track well with other available data, such as the statistics on payroll taxes reported by the Internal Revenue Service, independent of the BLS.

Burrowing into Friday's jobs statistics indicates that the economy is much closer to recession than the White House might wish to admit. The only significant gain in July was in the healthcare and social assistance sector (social assistance encompasses child care, vocational rehabilitation and food and housing assistance, among other job categories).

That sector saw a gain of about 79,000 jobs — accounting, in other words, for all of the overall job gains. Manufacturing, the sector that supposedly is the beneficiary of Trump's tariff policy, saw a decline of 11,000 jobs, its third straight monthly job loss, following a decline of 15,000 in June and 11,000 in May.

Put it all together, and the U.S. economy is in dire straits, possibly heading toward a shoal. Things aren't helped by an uptick in inflation, due to tariff-caused instability.

The combination of higher prices and lower growth presents a quandary for the Fed as it contemplates whether to reduce interest rates at the September meeting of its Open Market Committee, which makes the interest rate decision. The unanswered question is whether we are facing a stagnating economy, which might trigger an interest rate cut, or the dreaded stagflation, in which the economy grinds to a halt but inflation persists.

Either way, it's not good news for Trump, or the rest of us. He may soon run out of people to fire because he doesn't like their numbers.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments