From Gettysburg to Minneapolis: How the American Civil War continues to shape how we understand contemporary political conflicts and their dangers

Published in Political News

The negative public reaction to Operation Metro Surge – the violent immigration dragnet in Minnesota – was “MAGA’s Gettysburg,” wrote New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie on Jan. 28.

Bouie, of course, was comparing ICE’s setbacks to the Confederate defeat at Gettysburg, the battle often credited with turning the tide of the American Civil War. Fresh off a string of victories, Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, believed his men were “invincible” and launched an invasion into the North.

But Gen. George G. Meade and the Army of the Potomac won the battle of Gettysburg, and the Confederates would fight on the defensive for the rest of the war.

Since early 2026, growing numbers of commentators have turned to the Civil War of 1861 to 1865 to make sense of America’s fractured political climate.

After a masked federal agent shot and killed a 37-year-old mother of three, Renée Good, in Minneapolis, novelist Thane Rosenbaum wondered whether the city might become a “new Antietam.” The battle of Antietam, fought on Sept. 17, 1862, remains the bloodiest day in all of American history, leaving more than 3,600 soldiers dead.

Later in January 2026, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz speculated that ICE violence in the Twin Cities could spark a national conflict. “I mean, is this a Fort Sumter?” he asked an interviewer, alluding to the South Carolina harbor fortress where, in 1861, the opening shots of the Civil War were fired.

In response, defenders of Donald Trump, including CNN commentator Scott Jennings and House Majority Whip Tom Emmer, compared Walz to Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America. On Fox News, Washington Examiner columnist Tiana Lowe Doescher said: “News flash, Tim Walz. In this case, you’re the Confederacy,” accusing him of conspiring to defy federal immigration policy.

At a time of deepening national division, the recent spate of Civil War analogies should come as no surprise.

The Civil War remains the nation’s most divisive and defining epoch. The secession of 11 states propelled a democratic nation into unprecedented political fracture. After four years of bloodshed, the Union was preserved and 4 million enslaved people were granted their freedom.

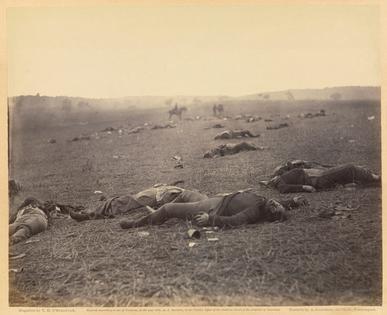

Preservation of the Union came at a heavy price. More than 700,000 people were dead, about 2% of the 1860 population, or a number roughly equivalent to the current population of the state of Maryland.

But the Civil War’s staggering death toll cannot fully explain the references to “Gettysburg” and “Jeff Davis” in media coverage of ICE operations in Minnesota and elsewhere.

As we argue in our book, “They Are Dead and Yet They Live: Civil War Memories in a Polarized America,” the impulse to connect the American Civil War to contemporary crises can be traced to the politics of memory, the ways interest groups, politicians and ordinary people shape the past to meet the needs of the present.

Likening Walz to Jefferson Davis or Minneapolis to Gettysburg or Fort Sumter are clear examples of how Americans appropriate the Civil War for our contemporary political needs.

In the Civil War’s aftermath, the conflict’s participants quickly crafted competing versions of the Civil War.

Some Union veterans labeled their former adversaries as traitors. Clinton Spencer, a captain in the 1st Michigan Infantry, declared, “disloyalty to the old flag was is and shall always be TREASON, deep, dark, and damnable.”

Yet the Union memory soon became subsumed by the dominance of the “Lost Cause,” an intentional and distorted narrative crafted by white Southerners. That version of the Civil War ignored slavery and celebrated Confederate soldiers in a war to defend states’ rights from federal tyranny.

By the early 1900s, Lost Cause ideology had taken root across the nation. The United Daughters of the Confederacy and other Southern apologists erected hundreds of Confederate monuments throughout the United States, and blockbuster movies like “The Birth of a Nation,” from 1915, and “Gone with the Wind,” from 1939, turned Lost Cause nostalgia into big-screen spectacle.

Over the past few decades, however, communities around the United States have made great strides to disentangle the Lost Cause from public memories of the Civil War.

After Dylann Roof massacred nine African American worshippers at Charleston’s Emmanuel AME Church in 2015, he was found to have espoused white supremacist ideas and posted a photo of the Confederate battle flag on his website. In the killings’ aftermath, cities across the South removed more than 300 Confederate flags, monuments and symbols from public view.

“The Confederacy was on the wrong side of history and humanity,” declared New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu in a 2017 speech about the removal of four Confederate statues in the city. “It sought to tear apart our nation and subjugate our fellow Americans to slavery. This is a history we should never forget and one that we should never, ever again put on a pedestal to be revered.”

In 1961, poet Robert Penn Warren famously observed, “Many clear and objective facts about America are best understood by reference to the Civil War.”

That remains the case today.

For many Americans, the Civil War is the prime example of the danger of allowing political division to spiral into organized violence.

Minnesota’s governor, Walz, could have used the sinking of the USS Maine in 1898 or the bombing at Pearl Harbor in 1941 for his historical analogy, but the references to the start of the Spanish-American War or World War II would not have been as powerful. Using the Civil War as a reference point underscores the danger when Americans decide to abandon their shared history and values and engage in fratricidal war.

Many of the recent Civil War analogies do not hold up to scrutiny. The events going on in Minneapolis bear little to no resemblance to the years of tumult leading to the assault on Fort Sumter, and the violence on the streets of Minneapolis can hardly compare to the horrors on the fields along the Antietam Creek.

But that’s beside the point.

More than 160 years after the defeat of Confederate forces at Gettysburg, the Civil War continues to have an enduring hold on the American political consciousness – shaping the way we view the past and offering a vocabulary for understanding the political conflicts of the present.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: John M. Kinder, Oklahoma State University and Jennifer Murray, Shepherd University

Read more:

How the 9/11 terrorist attacks shaped ICE’s immigration strategy

‘Which Side Are You On?’: American protest songs have emboldened social movements for generations, from coal country to Minneapolis

A government can choose to investigate the killing of a protester − or choose to blame the victim and pin it all on ‘domestic terrorism’

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments