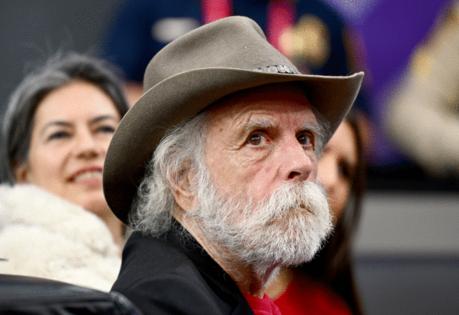

Q&A: Don Was talks Pan-Detroit Ensemble and its Grateful Dead-focused tour

Published in Entertainment News

PITTSBURGH — Going from playing in a band like Was (Not Was) to working with Bonnie Raitt and then playing with the Grateful Dead is quite the stretch, but it makes perfect sense for a musician like Don Was who's always followed the groove.

The Detroit legend, who is best known for what he's done as a producer behind the scenes, is currently on the road with Don Was and the Pan-Detroit Ensemble, performing material from its 2025 debut "Groove in the Face of Adversity" along with its interpretation of the Dead's funky and wildly uneven 1975 album "Blues for Allah."

Was, whose real name is Don Fagenson, grew up on sublime Detroit music that ranged from garage rock to Motown. He hit the scene in the early '80s with Was (Not Was), an art-funk ensemble with a baffling name and unruly sound exemplified by the apocalyptic dance workout "Walk the Dinosaur."

Nothing remotely like that was heard on "Nick of Time," the polished 1989 album he produced that made a supposedly washed-up Bonnie Raitt an album of the year Grammy winner. From there, his studio career took off as he went on to produce nearly 100 albums from the likes of the B-52s, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Brian Wilson, Elton John, Detroit's Iggy Pop and eight by one of his favorite bands, the Rolling Stones.

In 2008, the bassist-producer got back to the performance side with "Boo!," the first Was (Not Was) album in 18 years. And in 2018, he joined the Grateful Dead's Bob Weir and drummer Jay Lane in the touring band Wolf Bros.

Now, he is leading Don Was and the Pan-Detroit Ensemble, which unleashes all their hard-scrabble Motor City chops on jazz, funk and soul grooves.

In advance of the show Friday at the Thunderbird Music Hall and before the passing of Bob Weir, Was talked about the new project and the tour's dual focus.

Q: Watching that halftime show with Jack White and Eminem, I was reminded of the incredible music that has come out of Detroit. You grew up in that. What do you think accounted for Detroit being such a great music town?

A: I think a lot of it has to do with Detroit being an industry town. Certainly when I was growing up, it was. And everyone was in the same boat economically. You didn't have to work on the assembly line to have your fate attached to the success or failure of the auto business in any given year. And when everyone's in the same boat, there's a certain lack of pretension and affectation that just goes out the window, because it's pointless. When I was a little kid, there was absolutely no point in leasing a Mercedes to impress your friends because no one was going to be impressed. Everyone knew exactly who you were. So, it's a very honest population. Actually, not dissimilar to Pittsburgh. A lot of it just has to do with being a working-class town.

And I think that characterizes the music that came out of there, where John Lee Hooker, as the seminal Detroit musician, was as raw and unpretentious as you could be without the music completely falling apart. But it never fell apart. It would swing like crazy, and he was one of the most soulful cats ever, but just raw and honest, and what you see is what you get.

So I think in every field of music that's come out of Detroit, whether it's someone like Elvin Jones in the jazz world, or the MC5, or the Stooges, or Jack White in the rock 'n' roll world, or George Clinton, or Fortune Records, or J Dilla in R&B, it's the same thing. It's just raw, honest music with a deep groove.

Q: When did you become aware that there was this local Detroit music scene?

A: Probably Mitch Ryder. You know, Mitch Ryder was a guy ... you could have caught him playing at someone's wedding at one point in the '60s when they were Billy Lee and the Rivieras, and he burst out of Detroit playing this blue-eyed soul music combined with garage-band guitar aesthetic. And I don't know that anyone had done that really before him. And it was clearly something that only could have come out of Detroit. He even put it in the name of the band, the Detroit Wheels, and there's a tremendous amount of pride in that. Same with Motown. When I was a kid, when a Motown artist got a No. 1 record on the national charts, that was like the Detroit Tigers winning the pennant. You felt that they were representing you. And, yeah, that was a victory for the whole city.

Q :Tell me about The Pan-Detroit ensemble and what you set out to do with that.

A: Sure. Well, Terence Blanchard called me. He was curating a concert series for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and asked if I wanted to play one of the nights. And I didn't have a band together and didn't have any songs together, but I said yes and as it was coming close, I was starting to panic. And I remembered a lesson I learned when I was in the role as a producer back in '89-'90. I got to work with all of my heroes in very short order, from Bob Dylan, to the Stones, to Brian Wilson, to Leonard Cohen, to Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson. Just the best writers that I know of, you know?

I got to watch them work, but it gave me writer's block for about five years. Every time I sat down at the piano, I'd give up after 15 seconds and just say, 'Well, let's just give this lyric to Brian Wilson. He lives a half a mile away.' But after about five years, I was in the studio one day, again, lamenting the same thing with Willie Nelson. I was thinking, 'Man, I can never be him.'

And then it hit me, the converse: He can never be me. He didn't drop acid and go see the MC5 and the Stooges at the Grand Ballroom. He didn't have George Clinton and the Parliaments play a sock hop in his junior high school in 1965. So, what I learned then is that the thing that makes you different from everybody is not a marketing problem, it's actually your superpower, and that artists should identify the thing that makes them different from everybody else and become the best version of that that they can be. And I've always preached that to the artists on Blue Note or the artists I was producing. So I decided to apply it to my own case.

And when Terrence offered me this gig. I thought, 'Be the guy from Detroit. Go back to Detroit, find a room full of like-minded musicians who grew up listening to the same radio stations, who grew up playing in the same bars, playing with the same bands, and speak the common musical language of Detroit,' — which we already know has got a global appeal.

Q: And what was that process like?

A: It was easy as [expletive], man. I just called eight people who I loved and knew, a couple of whom I'd been playing with for 45 years, and we got into the room. There was a lot of suspense about whether it was going to work or not, but after about 10 minutes, it felt like we'd been playing together for 30 years because we had all this common musical language. And it just fell into place. And right then, within 10 minutes, I knew that this is a gift that you don't get too many times in life. Don't throw this away. So we booked a tour around it and we've been going ever since.

Q: How was the material generated?

A: Randomly. There wasn't a master design, really. In the first rehearsal, I just wanted to see the kind of stylistic breadth the band would have, how many different types of music could we tap into and still sound like ourselves, so I brought in a Cameo song and a Yusef Lateef song. And that was part of the thing: It didn't matter what kind of song we played, it sounded like these nine people playing.

Q: So, these are guys with jazz and R&B backgrounds?

A: Yeah, and all of them are different. A couple come out of a church background, really. But yeah, it's Detroit. I used to play with Wayne Kramer a lot. He was a good friend and when we'd play MC5 songs, I wanted to play it right. So I asked them to let me hear the multi-track so I could really hear what Michael Davis was doing. And if you broke the MC5 down to just bass and drums, it could have been an R&B record. It had a deep kind of groove to it, and the same with the Stooges. They were just like a garage-band version of James Brown, a hypnotic groove.

Q: I never thought of it that way, really.

A: Yeah, I think Iggy's best songs, they're groove songs. It's like James Brown. And to be honest with you, if you go back and look at some of the Stooges' films — if you can find it — he was every bit as compelling the frontman as James Brown was, you know, in a different way.

Q: Right, but without a shirt.

A: Without a shirt and no cape.

I've played on stage with Iggy a few times and it's so [expletive] intense, man. One time I remember him coming out on stage and kicking over people's music stands and he kicked someone who was leaning over the stage. He scared me. I was terrified by the energy that he was able to generate.

Q: So, how did you end up in the Grateful Dead orbit?

A: Well, Rob Wasserman introduced me to [Bob] Weir in the '90s. And we'd bump into each other from time to time. And when I got the gig at Blue Note, he and Mickey Hart came to see me about releasing some of their solo music. And I just finished doing a couple albums with John Mayer, and John was downstairs just writing songs in the Capitol Studios. So Mickey and Bobby were in the office — and I knew from every time I got in John's car, he had the Grateful Dead Channel, the Sirius channel, on — and he's one of those guys who could say, 'No, no, that wasn't May of 1978 because Jerry didn't get that pedal until August.'

So, I called him up in the studio downstairs. I said, 'You got to come up to my office, man. You won't believe who's here.' And they clicked. And I drove up with him for what was ostensibly his audition for Dead and Company.

Q: Geez, you were the connection for that. Wow.

A: Yeah, I introduced them. It was fantastic. The only thing I regret is, I didn't do what John did. John shut down his songwriting, cleared his equipment out, went home and practiced for three months. And so when he got to Bobby's place, man, he had internalized this music even more than he had as a fan and was ready to play. And I probably could have had the gig as the bass player, except I didn't do any of that. I just thought, 'Yeah, I know these songs.' And I didn't know the songs. And Mike Gordon was there one day and played and I played one day and I made the Grateful Dead sound like a bar tribute band.

Q: Ah, not in a good way?

A: No, in a terrible way. So, they made the right choice putting Oteil [Burbridge] in there, but I'll learn from John's work ethic, man. You know, show up prepared.

So two years later, Bobby called me and said he had a dream that Rob Wasserman came to him and said the reason he introduced us in the '90s was that I was supposed to take his place in Bobby's band after he was gone. And he had the name of the band and everything from that dream, the Wolf Brothers. And he said, 'So you want to start a trio? It's me and Jay Lane.' I was like, 'Yeah, of course, man.' I said, 'But tell me six songs to learn and let me focus on those and show up prepared.'

So he gave me six songs and we didn't play any of them when I got there. But I checked in The Bowery Hotel and rented a bass from David Gage and I did nothing but play these songs for like 12 hours a day in the 10 days leading up to going to see Bobby. So I was ready to play with them. And we didn't play any of the six songs, but we just started jamming on an A-minor and after about 15 minutes it was clear that we had a thing,

Q: We only have a few minutes, so I better ask you about 'Blues for Allah,' and your approach to that. One of the more unusual Dead albums for sure.

A: Yep, yeah, definitely. Well, I think it's a really cool record, and stuff that I thought was perhaps a meandering improvisation, if you actually dig into it —which I did once we took on the mission of playing the stuff — there's a real structure. Like, 'Solomon's Marbles,' man, I couldn't figure out what the [expletive] was going on there. How are we going to play that? But there's actually a real strict form to that.

The challenge, once I understood that there was shape to everything, was what you don't want to do is, you don't want to be karaoke Grateful Dead. So how can this band be themselves and play these songs as if we'd written them but still stay true to the ethos behind the whole album? Uh, I think we found a way in that's pretty cool. And it varies from song to song.

'The Music Never Stopped,' man, you don't have to do much to that. We play that the way we play it and we don't have to veer that far from what The Grateful Dead did. But some of the other ones, 'Blues for Allah' and certainly 'King Solomon's Marbles,' we found our own way into it that people will recognize the song but we play it as if we'd written it.

Q: Is it one of your favorite Grateful Dead albums or, like, where does it rank for you?

A: I never viewed it in the same light as, like, 'Workingman's Dead,' but there's a lot more to it than meets the eye. And the more we play these songs, the more meat I realize is on the bone. And there are a number of ways to play these things and to approach them fresh every night, which is where the fun is. That's the adventure. We know how they go, but where are you going to take them every night?

© 2026 the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Visit www.post-gazette.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments