This California political leader wants federal immigration reform. First, she has to survive Trump

Published in News & Features

Since President Trump's immigration raids began sweeping through California's cities and farm fields, state Senate President Monique Limón has carried a copy of her passport.

"Just in case," she said.

Limón is one of the most powerful politicians in the state behind Gov. Gavin Newsom, but the detainment of American citizens, including U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla — who was handcuffed by federal agents in Los Angeles in June — showed that no Latino in California is safe.

In July, a farmworker in the country illegally fell to his death during an immigration raid in Camarillo, part of her district, and fear of other sweeps prompted the recent cancellation of a holiday parade in her hometown of Santa Barbara.

Locals have been detained while walking to the grocery store, she said.

"There's this fear of racial profiling that is happening that I think is very real," said Limón, 46.

The granddaughter of a Mexican farmworker and the first Latina elected Senate president, Limón ascended to the post in November after a tumultuous year that saw the Democratic-led state under constant attack from Trump and the Republican leadership in Congress.

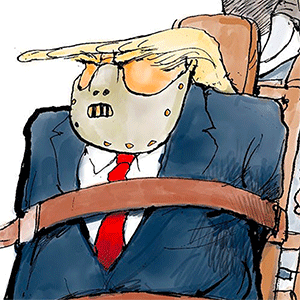

The coming months will test Limón as the Trump administration ramps up deportations, looks to expand offshore drilling off the Santa Barbara coastline and slashes federal funding for Medicaid and other programs.

Limón, a progressive Democrat, must also work alongside Newsom, who is likely to use his final year as governor to strengthen his reputation as a presidential contender and may clash with Limón and other legislators over budget decisions.

A state budget deficit, caused in part by the expansion of Medi-Cal and other Democratic priorities, will also challenge lawmakers hoping to backfill cuts by the Trump administration.

"It's a difficult time for California," said Limón, who lives in unincorporated Santa Barbara County and is married with a young daughter. "Not just our state, but I think the country as a whole.'

On Friday, Limón joined immigration advocates outside a U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in Santa Maria to demand answers about the detainment of nearly 150 people in Limón's central coastal district in late December.

"We can't let what's happening be something that we normalize," Limón said.

Raids last year targeted farms in Limón's district, an area that includes all of Santa Barbara County and parts of San Luis Obispo and Ventura counties.

For Limón, the fight for immigrant rights is deeply personal.

Limón's grandfather picked strawberries in Oxnard after coming to the U.S. through the state's bracero program. The senator draws a link between California's economy and its undocumented workforce, blaming labor shortages and unharvested crops on the raids.

"We need federal immigration reform," Limón said. "And that includes a comprehensive look at the state of immigration, the benefit of immigration, the benefit of our immigrant community.

"That is not just in all the taxes they pay, but certainly their contributions to so many sectors of our economy as well."

A 2019 study by the federal government estimated half of all of the state's farmworkers are undocumented and the vast majority of workers are from Mexico.

Limón remembered Jaime Alanis Garcia, the farmworker who died in Camarillo in July, in a speech on the Senate floor. She described Garcia calling his family in his final moments and telling them how scared he was.

"After 30 years of working in this country as a farmworker, doing the job that our government, our country, our constituents, has called an essential worker job, that his life would end that day, that way, because of where he was working," said Limón.

A Department of Homeland Security spokesperson said in a statement that more than 10,000 alleged undocumented immigrants have been arrested in Los Angeles since Trump took office last year, but the agency didn't provide statewide numbers.

DHS "has arrested and deported hundreds of thousands of criminal illegal aliens across the country, including gang members, rapists, kidnappers, and drug traffickers.

"DHS is just getting started under President Donald Trump and Secretary (Kristi) Noem," the statement said. "The best is yet to come."

Limón said "it's not lost" on her that the granddaughter of immigrants is helping lead the state at a time when Trump wants to remove Mexicans from California.

Growing up in Santa Barbara, she marched with her parents against Proposition 187, the 1994 ballot measure which denied many taxpayer-funded services to undocumented immigrants.

The coastal city was also the site of a massive oil spill in 1969 that killed thousands of birds, fish and sea mammals, and helped launch the state's environmental movement.

Limón's own interest in environmentalism was sparked, she said, by the wildfires that erupted in the nearby Santa Ynez Mountains and forced school classes to stay indoors, she said.

The first person in her family to go to college, Limón attended UC Berkeley and received a master's degree in education from Columbia University.

Petite in stature, she describes herself as an "accidental politician" whose interest in higher education led her to run for her local school board, which led to a campaign for state Assembly, and later, state Senate.

Colleagues, including some Republicans, describe her as reasonable and a policy wonk who loves spreadsheets.

Sen. Henry Stern, D-Los Angeles, who has worked with Limón to target oil drilling, said she is a "lower-key kind person" who doesn't seek out the spotlight.

"She doesn't have that pushiness that many politicians tend to have, which is 'Who is in the front, who gets to be on TV?'" he said.

Former Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez, who now heads the California Labor Federation, recalled Limón's uphill effort to pass a bill to stop predatory lending. The legislation died the previous session, and support waned.

Gonzalez asked her how she was going to get the votes.

"She said, 'I am asking you to trust me and let me work this,'" Gonzalez said. The bill passed with bipartisan support and caps interest rates on consumer loans.

Her other high-profile bills include requiring employers to disclose pay ranges in job ads and allowing child-care workers to unionize.

She has frustrated pro-housing groups by declining to vote on some bills, including one to allow more density near transit stops, and by her push to force an environmental review for a controversial development in her Santa Barbara hometown.

In November, she criticized the Trump administration over its announcement to open up the coast to offshore drilling, arguing "new offshore drilling leases lock us into decades of pollution."

Some of her relatives are politically conservative and she gets an array of questions at family gatherings: "Why didn't California do this? I heard on the news that this is happening. What does this mean?"

Her extended family is so large that a recent Thanksgiving of nearly 40 family members was considered small.

Her aunt, Mónica Gil, an executive at NBCUniversal Telemundo, introduced Limón at a gala in December to honor her in downtown Los Angeles. During her speech, Limón reminded the crowd that it took 175 years for a woman with her background to be elected Senate president.

"We are starting to see the glass ceiling crack," said Limón. "We're not there yet, but that glass ceiling that's cracking is opening doors."

Former state Sen. Kevin de León was the first Latino elected Senate president, and the author of the state's sanctuary law, which limits state and local government cooperation with federal immigration enforcement.

Complicating the state's budget process is an anticipated shortfall in the coming year.

Sen. Roger Niello, R-Fair Oaks, vice chair of the budget and fiscal review committee, expressed alarm that California's expenditures continue to outpace revenues, even though the state isn't in a recession.

He predicted Limón will be a "good pro tem for Republicans to try to collaborate with" because she "will listen to people."

The state budget divided some Democrats last year when Newsom proposed ending new Medi-Cal enrollments for some undocumented groups and requiring others to pay monthly premiums. The majority of the Legislature, including Limón, backed the changes.

Sen. María Elena Durazo, D-Los Angeles, a member of the Latino Caucus, opposed the move and chastised her colleagues for the "betrayal." "Remember today's date and what the Senate is doing," said Durazo during a speech from the Senate floor.

Limón said her starting point with the new budget is to try and "keep the existing programs in place that help Californians without having to do reductions or cuts."

In early December, dozens of immigrants rights' advocates met with Limón's staff to present their priorities for the budget.

The Trump administration last year secured tens of billions of dollars in government funding to hire more immigration officers and build detention centers — infrastructure intended to speed up deportations.

Some advocates want at least $150 million for immigrant legal services in California's budget, money that would follow an initial outlay last year.

"There is going to be need for permanent funding (for legal services) throughout the Trump administration," said Masih Fouladi, executive director of the California Immigrant Policy Center, who attended the meeting.

Durazo also wants more money for attorneys.

"It actually stops people from getting deported," said Durazo. "We learned from what worked."

While the arrests have brought attention to California's field workers and day laborers, Limón said students and others also need a pathway to citizenship.

"That is only going to come from the federal government," she said.

_____

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments