Despite moves by Indiana lawmakers, Illinois' borders are unlikely to change. Here's why

Published in News & Features

CHICAGO — Don’t hold your breath, Hoosiers.

The nearly three dozen Illinois counties where a majority of voters in recent years have expressed their desire to leave the Land of Lincoln won’t be joining their neighbor to the east anytime soon — or probably ever — regardless of any recommendation from a bistate commission Indiana Gov. Mike Braun signed off on last month to study the issue.

While the measure creating the commission sailed through the Republican-dominated Indiana statehouse on its way to the GOP governor’s desk, a companion proposal from one of Illinois’ most conservative state lawmakers went nowhere in the Democratic-controlled General Assembly before it adjourned its spring session.

The disparate responses in Indianapolis and Springfield to the proposed creation of an Indiana-Illinois Boundary Adjustment Commission, described by supporters as a conversation starter but decried by critics as a pointless political stunt, are emblematic of the yawning political divide between the states despite their deep geographic and economic ties.

Here’s a look at how we got here and what comes next.

Constitutional requirement

When it comes to changing existing state boundaries, the U.S. Constitution is fairly clear.

Article IV Section 3 reads: “No new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.”

In plain English, that means the 33 Illinois counties that have had successful — though nonbinding — referendums seeking secession can’t join Indiana without the approval of each state’s legislature and of Congress. And if they wanted to form their own new state, the counties still would need lawmakers in both Springfield and Washington, D.C., along with Illinois’ governor and the president, to sign off.

Such changes aren’t entirely unprecedented. Kentucky, for example, joined the Union in 1792 after its breakaway from Virginia was approved in the state legislature and Congress. Similarly, Massachusetts lawmakers gave their approval for Maine to become its own state, a move that Congress formalized in 1820 as part of the Missouri Compromise, which also admitted Illinois’ southwestern neighbor as a slave state.

One state, however, did manage to carve itself out of an existing state without strictly adhering to the process laid out in the Constitution: West Virginia. But that move came amid the Civil War, after Virginia seceded from the Union and its capital became the seat of the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln signed a measure creating the state of West Virginia in 1863. After Virginia was readmitted to the Union, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld West Virginia’s statehood.

Secessionist sentiments

Regional animosities have existed in Illinois since before it was admitted to the Union in 1818 as the 21st state and only grew stronger with Chicago’s rise as an economic powerhouse in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, according to a 2022 report from the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University.

After the state narrowly voted in 1860 to send Lincoln from Springfield to the White House, Confederate sympathies lingered in some areas. Union troops were stationed in the southern Illinois town of Olney to enforce the draft, and a deadly clash between Union soldiers and pro-slavery Copperheads broke out in Charleston, now home to Eastern Illinois University, in 1864.

Over the 160 years since the Civil War ended, the urge to separate has bubbled up from time to time. The Chicago City Council in 1925 passed a resolution to look into secession over concerns about the city’s representation in Springfield; residents of western Illinois in the 1960s and ’70s created the tongue-in-cheek Republic of Forgottonia; and the state Senate in 1981 approved a Democratic legislator’s facetious resolution urging Congress to make Chicago and the rest of Cook County “New Illinois,” the 51st state.

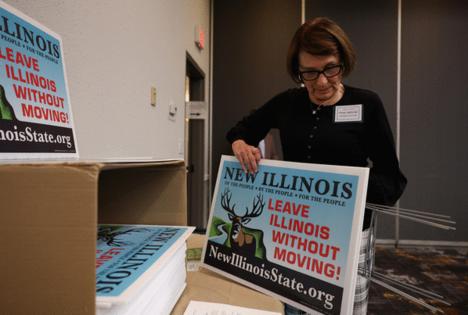

In the Donald Trump era, as Democrats have firmly consolidated their control of Illinois government, some on the political right, largely downstaters, have picked up the “New Illinois” mantle, pushing unsuccessful state legislation and successful but legally weightless countywide resolutions seeking to cleave the state in two.

Most recently, in November voters in seven downstate counties — Iroquois on the Indiana border and Calhoun, Clinton, Greene, Jersey, Madison and Perry near the Missouri state line — approved ballot measures calling for a divorce from Chicago and Cook County.

Indiana’s invitation

The recent rumblings from downstate Illinois have caught the attention of lawmakers across the border in Indiana, where dominant Republicans are eager to position their state as a low-tax, low-regulation alternative to deep-blue Illinois.

In the only bill he introduced during the spring session, Indiana House Speaker Todd Huston called for the creation of a bistate commission “to discuss and recommend whether it is advisable to adjust the boundaries between the two states.”

“These people (in downstate Illinois) literally went and voted. They have spoken,” Huston told the Post-Tribune in January. “Whether Indiana is the right solution or not, they’ve expressed their displeasure. We’re just saying, if you’ve expressed your displeasure, we’d love to have you.”

Originally calling for equal representation from each state, the measure was modified as it became clear Illinois Democrats weren’t having it. The final version Braun signed into law, opposed by Democrats and a few Republicans in his state, gives Indiana a one-seat majority on the panel, allowing it to meet without any input from Illinois.

Under the Indiana law, Braun must appoint six members to the commission, notifying Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker of his selections, and schedule its first meeting by Sept. 1.

Illinois’ response

When the Indiana proposal made headlines early this year, it quickly became clear, if there was ever any doubt, that Illinois Democrats had no interest in playing along.

“It’s a stunt. It’s not going to happen,” Pritzker said at an unrelated news conference in January. “But I’ll just say that Indiana is a low-wage state that doesn’t protect workers, a state that does not provide health care for people in need, and so I don’t think it’s very attractive for anybody in Illinois.”

Even those pushing hardest for an Illinois breakup don’t appear overly eager to be subsumed into Indiana.

“Our goal is the constitutional formation of a new state separate from Illinois,” G.H. Merritt, who leads the group New Illinois, told Indiana lawmakers at a hearing in February, the Post-Tribune reported.

Nevertheless, in the Illinois House, Republican Rep. Brad Halbrook of Shelbyville, a member of the ultraconservative state Freedom Caucus who in the past has filed resolutions calling for Chicago to become its own state, in January filed a proposal for Illinois to join Indiana in creating the boundary commission.

But Halbrook’s proposal was never given a hearing or even assigned to a committee this spring.

At a statehouse news conference during the closing days of the legislative session in late May, Halbrook and some of his Freedom Caucus colleagues bristled when asked how they hoped to move the conversation forward in Illinois when Democratic leaders won’t let the proposal see the light of day.

The real question, Rep. Blaine Wilhour of Beecher City said, is why the counties that have voted in favor of secession “want out of Illinois so bad?”

“That’s the question that you need to be asking,” Wilhour said. “But nobody asks it. They want out of Illinois because they’re not being respected by their government. Their government continues to push policies that drives away every one of their opportunities.”

Tacitly acknowledging the futility of the effort, Halbrook said, “We don’t need a new state; we need a new governor, and that’s the bottom line.”

Illinoisans will have a chance to elect a new governor next year. Pritzker, who has won two terms by double-digit margins, has yet to say whether he’ll seek a third.

____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments